MASS

David Kwaw Mensah

David Kwaw Mensah considers how Nadeem Din-Gabisi's MASS can be categorised in the genre of Transcendental Cinema.

Projects

Watch Nadeem Din-Gabisi's MASS in full here

On the one hand an enigmatic jewel of audio-visual storytelling and on the other a delicious dream sequence realised as a filmic experiment, musician, poet, painter, writer and director Nadeem Din-Gabisi’s MASS avoids casting itself in the mould of any specific generic paradigm. Stylistically, however, the works of Bela Tarr, Yasajiru Ozu and Andrei Tarkovsky specifically spring to mind, as do recent films by Apichatpong Weerasethakul. But what, one might ask, do these filmmakers have in common? The visual systems with which they compose their images all seemingly adhere to what filmmaker Paul Schrader and philosopher Gilles Deleuze have described as ‘Transcendental Filmmaking’. According to these thinkers, and other important critics such as Raymond Bellour, cinema tends to fall into one of two branches, the first being that films consist of ‘movement-images’ which, overall, means cutting exists within its style for the sake of continuity and for the placing of actions in relational time, with the second being the ‘time-image’, which in short is the department of filmmaking in which shots are the source of both the contemplation and the acknowledgement of poetry as time. The latter idea stems from the belief that film (especially in terms of the duration of a shot) can act as a form of photographic meditation. Often, in this type of cinema, there are certain objects which haunt the work at hand. For Tarr it is crumbling buildings, symptomatic of a world perpetually in a process of decay. For Ozu it is the kettle, its steam being a symbol for the ephemeral nature of life. For Nadeem Din-Gabisi it may be the very object that appears in the first shot of MASS; an analogue radio, framed by plants on either side. The table could easily be an altar. The radio itself could be deemed an object of worship by the person who turns its dial or the people who we are only made aware of by the sound of their clapping. Perhaps the radio personifies life at its most euphoric and we, the viewers, are being invited to celebrate.

If MASS can be categorised as a new addition to the database of 'Transcendental Filmmaking’ and thus is quantifiable as a vehicle for cinematic meditation, there still remains the question: what is the film meditating on?

Roughly 12 minutes in length, MASS compiles a tapestry of images which take, as their starting point, a theoretical term known as the ‘Black visual frequency,’ coined by academic Tina Campt. Shot using a combination of video, 16mm film and 8mm film, MASS takes Campt’s academic concept and makes it a tangible, living force, paints entire spaces with it, both urban and intimate, as well as harnesses the minds, voices and talents of numerous musicians, dancers and performers.

The film begins with said image: an analogue radio at the centre of a table. A sacred device resting in the grainy eye of a crackling frame. This comes after a wave of applause rings sharply from an unknown source. Singular piano notes play in minor keys. Are we looking at found footage from decades past? Arms of a mostly unseen subject enter the frame. They turn the dials. The fizzing and whirring of frequencies altering. Soundscapes shift and fluctuate. We hear voices in discussion, beats, a whole panoply of sonic textures. Is this a story about sound? When the hands finally stop changing the radio’s frequencies, we are treated to a stream of tranquil tempos where electronic charges are pulsating, stopping and starting, pulsating, stopping, starting, and on and on it goes; a relentless, unnerving, yet peaceful utterance. The music stays the same, yet the image changes. A sudden violent, Godardian, cut to white and we see what looks like an analogue film in the midst of a light leak. A swift yet pained transition like a quick death. We then come to a white room (is this the afterlife?). We are encountering butterflies on aerials, satellite dishes and hills of dirt. Technology and nature. There are seats which look like circular thrones with designs that are weaved as if ripples in water or, it might be said, like sound waves. Are we inside the radio, are we, perhaps, seeing what sound looks like from the interior? A jump cut and two figures appear, seated. A man in a white garment and a woman in black. Again we find opposites: Man/Woman, black/white, Yin and Yang. They play with the satellite dishes, they touch the earth, they hold hands. ’They are sense organs, although the exact nature of what they sense and how they sense is not the same in all groups, they convert electrical signals into radio waves and vice versa,’ a maternal voice-over tells us. Are the man and the woman transmitting signals to each other, are aerials, cables and black bodies all, similarly, distributors of electronic waves?

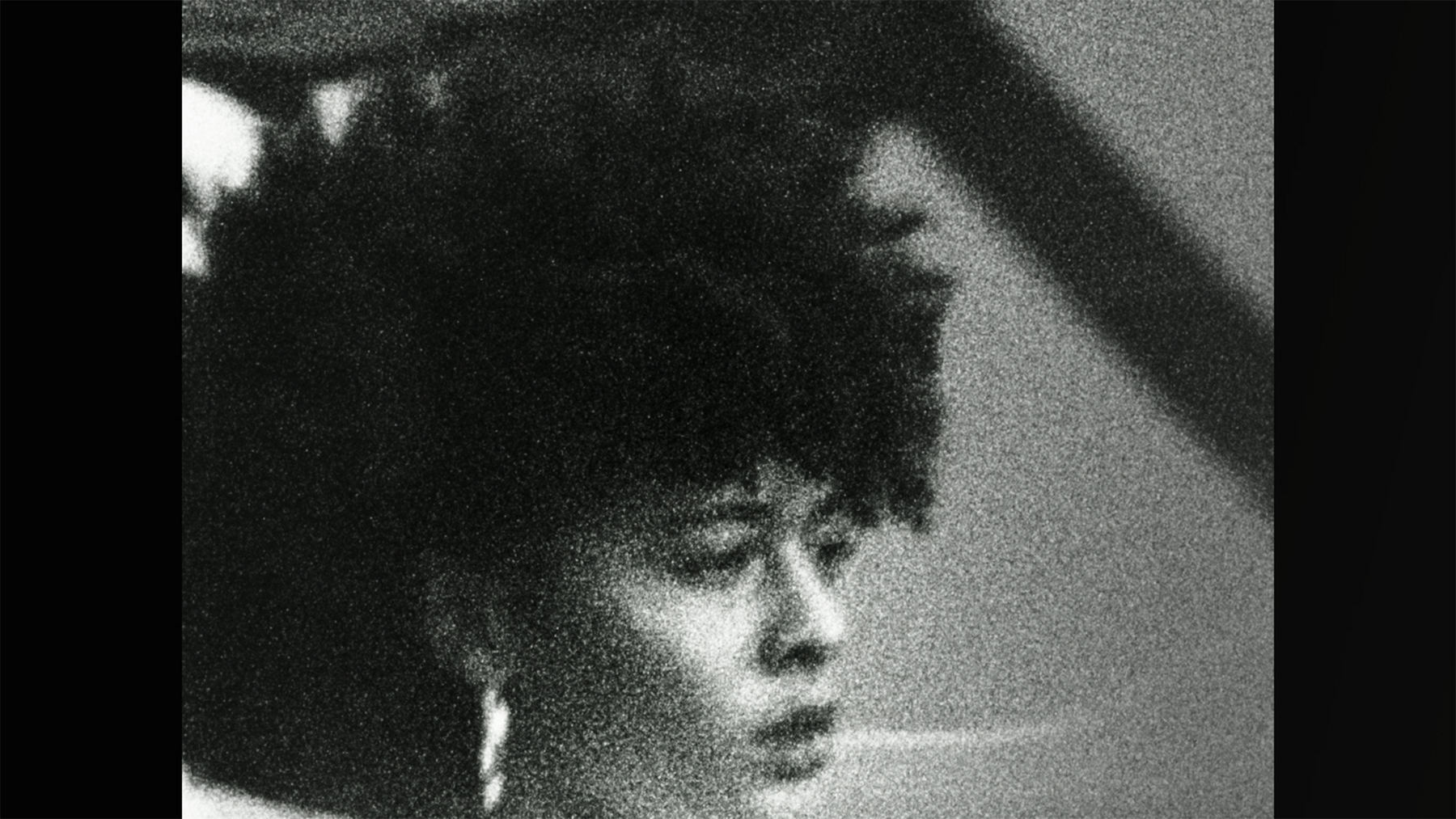

Meanwhile, a grainy, monochrome gaze explores inner city streets. Aerials and satellites dominate the skies above. A woman in black and white with penetrative eyes and afro hair walks along determinedly. She is the Seeker. Like the extra-terrestrial protagonist in Jonathan Glazer’s Under The Skin (2013) she is both other-worldly and, it seems, on a mission. Perhaps she is from another dimension or time or a goddess from an archetypal myth. Whoever or whatever she is, in a later scene she enters the white space (meaning she has travelled from a monochrome world to a colour one, like Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz) and becomes the unifying factor in what appears to be a type of Taoist trinity, a Yin/Yang triad in which the mysterious woman comes to represent both light and dark. In one of the closing shots the man in his white outfit, the woman in black and the mysterious lady in black and white all sit in perfect symmetrical harmony, as if this sacred space has, all along, been the temple and the catalyst for cosmic balance.

Perhaps it is ultimately the arrangement of these images that earns MASS its place in the database of Transcendental Cinema. Din-Gabisi’s directorial hand creates an effect that is hard to pin down, as if he has taken slices of documented reality and sculptured them into image poems. These add to the film’s wider structural agenda, which does not concern itself with plotting, exposition or conventional narration. Instead, the lens of MASS’s eye is fixed on exploring, fetishising, contemplating and meditating on the unity of that which is often considered to be in opposition, such as man and nature, nature and technology, light and shadow, Yin and Yang.

As there is no obvious main character in the film, the sole narrative arc belongs to us the viewers. It is our journey as well as it is the subject's within the film. It is us who, in theory, change the most. So not only is the film ‘Transcendental’, it is also deeply and beautifully transformative.

––

About David Kwaw Mensah: I like to refer to myself as a photo-poet/film enthusiast. I’m on a mission to write poetry with light as well as words. The once film editor of south London’s own Live Magazine and proud staff writer for Black Film and Media (BFM), Soul Culture, The Looking Glass Collective and the BFI’s Black World publication. My portrait photography, which continues to explore, humanise, deify and celebrate black faces in London has been exhibited at the Africa Centre as part of The Big Sixty (taking place in both London and Lagos), 50 Golbourne, TheOthers and Nooru Box in Paris as part of Afro Shoot's Bridged Narratives series. My event work has been featured in The Stage, whilst my documentary work has featured in Redull’s Amphiko series, which portrays the lives of people making a difference in their communities throughout the world. I see cinema as the cultural, ideological and spiritual mirror of humankind and I continue to write about the art and industry of film from this perspective. I’m currently undergoing the mammoth task of photographing London’s Notting Hill Carnival every year for ten years. The aim being to highlight the shifts in black culture in the UK over a ten year period as well as to produce a photographic love letter to future generations about our times. The images that I’ve created thus so far can be seen in the June 2019 edition of Black Joy Zine or on my blog: shortsightedblog.blogspot.com.

This text was written in response to MASS (2020) by Nadeem Din-Gabisi, commissioned for Frequencies, a curatorial project initiated by Cynthia Silveira. Commissioned and produced by Film and Video Umbrella (Producer Leah McGurk) as part of FVU's Curatorial Practice Award. FVU is supported by Arts Council England.