We Put The World Before You

Erika Balsom

Film theorist Erika Balsom takes a close-up of Jane and Louise Wilson's 2016 work We Put the World Before You.

Projects

ACCORDING TO FILM THEORIST JACQUES AUMONT, ‘To film a face is to confront all the problems of film, all of its aesthetic problems and therefore all of its ethical problems.’1 It would be easy to dismiss such a proclamation as overstatement, but returning to the first decades of the twentieth century provides support for Aumont’s wager. In the 1920s, while the Futurists looked to the aerial view as a distinctly modern form of vision, writers such as Béla Balázs and Jean Epstein looked to a different emerging technology, the cinema, and attempted to articulate its power. They found in it a transformative way of seeing that could make possible a revelatory encounter with the world. In particular, they were entranced by faces rendered gigantic through projection, amplified to a scale that dwarfs the viewer. The close-up, with its capacity for magnification and the making-visible of micro-movements, emblematised for these writers the specificity of this new medium—and the face, of course, is the close-up par excellence. In the wake of the horrors of World War One, the physiognomic vocation of cinema held a utopian promise of human understanding, a promise that would be often betrayed but never entirely vanquished in the century to come.

The face captured on camera occupies a central position in Jane and Louise Wilson’s We Put the World Before You (2016), a work in which disparate signifiers of historicity collide to produce an evocation of the mass entertainments and mass horrors of the World War One years infused with hints of the 1970s and the digital present. A group of women enter into a state of collective hypnosis led by a blonde man. ‘There’s a face there—a face that means something to you,’ he tells them, ‘Stare at the face. Imagine that you could go into that image. Become part of the face.’ As they relinquish conscious will and give themselves over to the incantatory voice of their leader, they are not unlike a cinema audience, entering the virtual world of the screen.

Although they are clad in attire reminiscent of the 1910s, certain sartorial details, along with the lurid pink and green light cast on their bodies, summon filmic associations of a much later time, of Luchino Visconti’s The Damned (1969) and Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Lola (1981), both films that sought to picture a past era with purposeful inauthenticity by marshalling the artifice of colour. The women make hand gestures that belong decidedly to the contemporary moment, holding imaginary smartphones and manipulating their imaginary touchscreens, as if to zoom in on an absent image—a very different form of magnification than the ungraspable grandeur of the cinematic close-up.

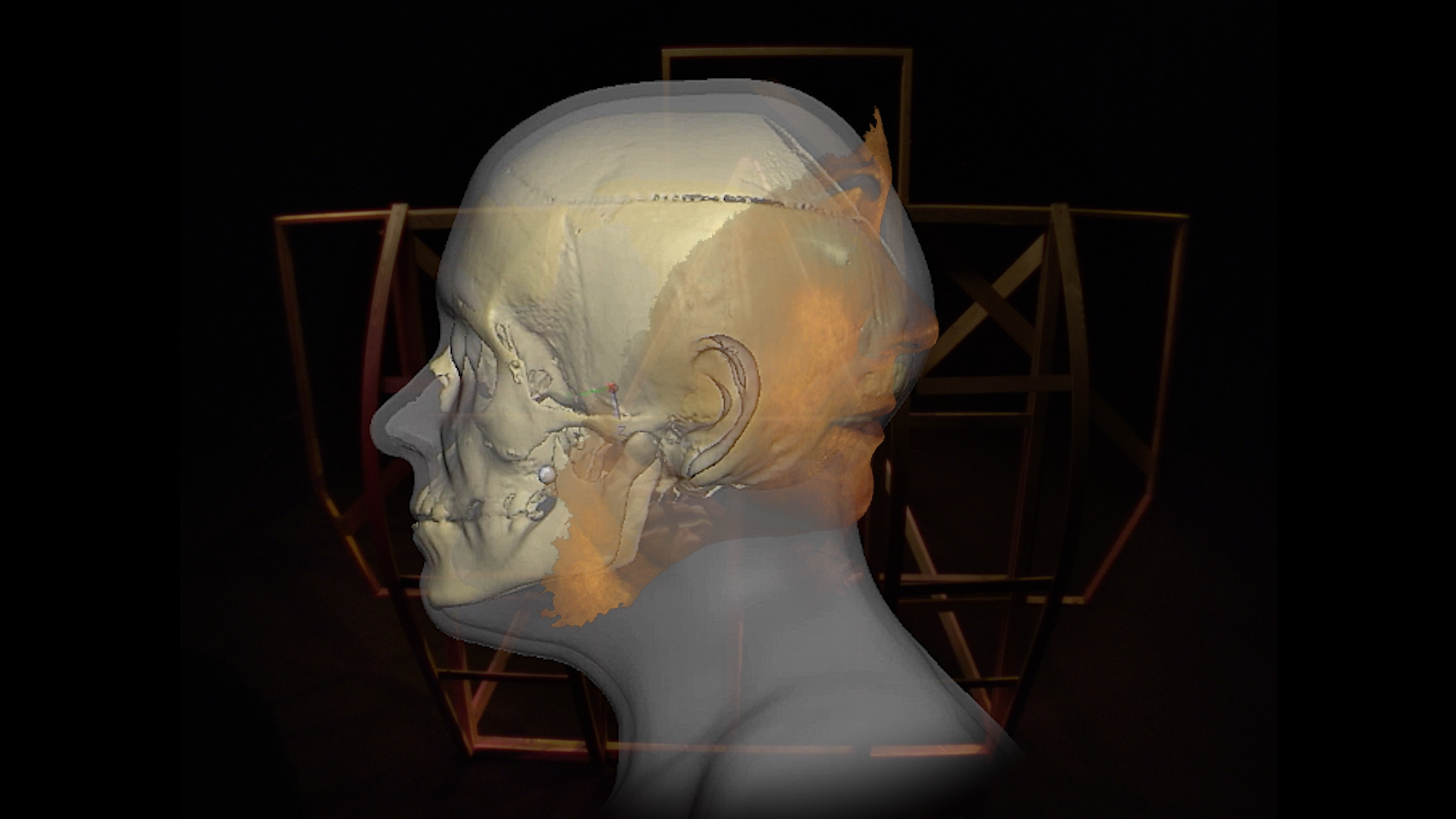

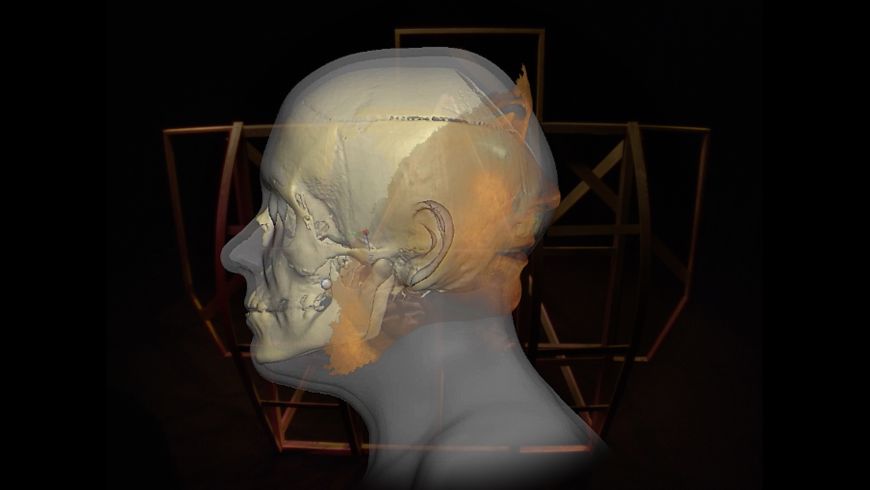

If, for Balázs, the face in close-up was a possibility of communion, today faces are just as likely to be scanned as they are to be filmed, stripped of their ineffable qualities and subject to algorithmic calculation for purposes of management and control. Extending the bricolage of temporalities already suggested in the production design of the hypnosis sequences, the Wilsons periodically insert digital renderings of their own faces—mask-like surfaces without depth, able to be rotated 360 degrees, detached from fleshy life. To close the film, recalling Undead Sun, the Wilsons offer a series of archival photographs of WW1 veterans with facial injuries that morph together to form the image of the ‘average’ soldier. Individual particularity gives way to typicality, and the archival photographs begin to resemble the composite portraiture undertaken by Francis Galton in the 1880s, a technique widely understood as a precursor to today’s mechanisms of biometric governance.

As in Undead Sun, in We Put the World Before You, a passage opens between past and present that allows one to trace the longer histories of technologies and techniques so often and yet so spuriously deemed in our time to be new. But this is not to suggest that the passage from 1918 to 2018 is one of simple continuity. The film’s title is borrowed from a slogan coined by Charles Urban, an early cinema pioneer who exploited scientific films as popular entertainment, gaining special fame for those relying on the spectacle of extreme magnification. These were films that would, in the words of Walter Benjamin, burst open the ‘prison-world’ of habitual vision with ‘the dynamite of the split second, so that now we can set off calmly on journeys of adventure among its far-flung debris.’2 The debris of mediated vision is still with us, but now it has been securitised, its emancipatory potential sapped. If the close-up was the apotheosis of the face, then in the biometric scan, quality gives way to quantity, and the face meets its end.

Endnotes

1.Jacques Aumont, “The Face in Close-Up,” The Visual Turn: Classical Film Theory and Art History, ed. Angela Dalle Vacche (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2003), 133.

2.Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility: Third Version,” Selected Writings: Volume 4, 1938–1940, ed. Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2003), 265.

–––

Erika Balsom is senior lecturer in film studies and liberal arts at King's College London. She is the author of Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art (2013) and the coeditor of Documentary Across Disciplines (2016).

This text was written in response to We Put The World Before You (2016) by Jane and Louise Wilson, which was commissioned by Film and Video Umbrella in partnership with Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art and Wolverhampton Art Gallery. Supported by Wellcome Trust and using public funding by Arts Council England.