Beer and Skittles

Steven Bode

Steven Bode has written a new text reflecting on the expansive life and practice of late artist Julie Henry, alongside the creation of her FVU-commissioned work This Sporting Life (2002).

Projects

‘The Indoor League’ was a popular television programme produced by the now-defunct Yorkshire Television that aired for six separate series from 1973 to 1978. As its name implies, it staked out a seat far away from the Grandstand view of the traditional sporting calendar and homed in instead on the world of pub sports (darts, pool, bar-billiards, table-football and the like) that were played with gusto in drinking establishments throughout the land but that were rarely, if ever, broadcast on TV. The brainchild of Sid Waddell, the original ‘Voice of Darts’, whose powers of persuasion and idiosyncratically flighted turns of phrase did so much to popularise the game, the show was filmed amid the workingmen’s club ambiance of the Irish Centre in Leeds and hosted by cricketing legend Fred Trueman, swapping his ‘Fiery Fred’ fast-bowling persona for cardigan and pipe, his archetypal yeoman Yorkshireman credentials expressed in a gruff leonine bonhomie that was not so much Michael Parkinson as Ted Hughes in panto.

The artist Julie Henry, who died earlier this year after a long illness, was a big fan of ‘The Indoor League’ – unsurprising given her longstanding passion for sport and her unstinting, instinctive feel for authentic cultural/communal experiences, especially those whose obvious appeal for their enthusiast participants didn’t always translate into a wider public profile. A rich and varied body of photographic, film/video and object-based work, latterly made in close collaboration with kindred spirit Debbie Bragg under the moniker Henry/Bragg, casts its eye over a crowded field of disparate activities: from pre- ‘X-Factor’ amateur talent shows to bingo nights and binge-drinking weekenders to examples of spare-time hobbyist creativity such as knitting circles or gardening clubs. Interspersed with exuberant blasts of punk music, Northern Soul and football terrace chants, these are portraits of the English working class at leisure and at play, both gloriously in the moment and unselfconsciously out of time. When Henry began exhibiting in the late 1990s it was still relatively uncommon for these facets of ‘ordinary’ working-class existence to be encountered, let alone celebrated, in the rarefied sphere of the art gallery; and more to the point, with an unmistakeable sense of solidarity and fellow feeling that radiated through every scene. Over the course of an exemplary thirty-year career Henry continued to strike an innately empathetic chord with her subjects, a quality that makes her work so compelling and affecting.

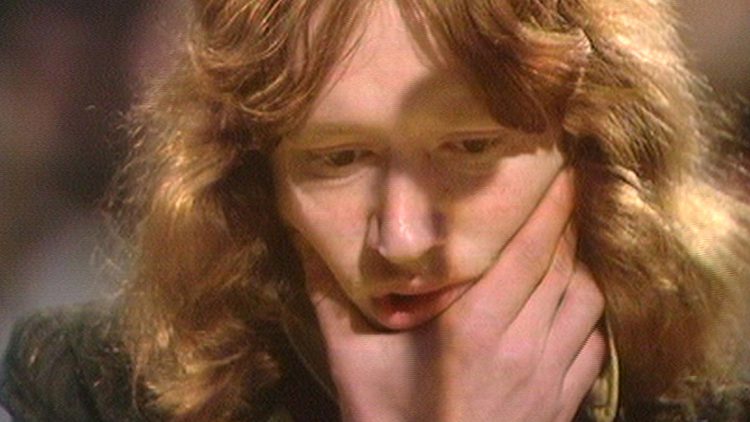

In her five-minute video, This Sporting Life (2002), Henry revisits one of the highlights from the first series of ‘The Indoor League’: the final of the table-skittles tournament between the veteran Dennis Jones and his young-buck adversary, the confusingly named Philip Senior. As if seen through the lens of a long-distance action replay, Henry subjects the nostalgic, almost ingenuous archive material to an exaggeratedly detailed after-the-event analysis, enlisting the original commentator Dave Lanning to supply a new voiceover, and adorning the footage with a bevy of informational graphics and video effects of a type that was becoming ubiquitous in the coverage of TV sport at the turn of the new millennium. This Sporting Life was commissioned by Film and Video Umbrella and Cornerhouse, Manchester for the group exhibition, ‘Spectator Sport’, and Henry’s video vividly describes the extent to which love-of-the-game absorption in sport can easily morph into armchair spectatorship and commodified spectacle. The arc of darts is a case in point: introduced to UK screens by ‘The Indoor League’ it was already well-embedded by the year 2000, no longer a demotic aside in Martin Amis novels, and, like snooker, a mainstream televisual staple. The last two years, though, have seen its profile soar ever further, beyond the nooks and corners of spit-and-sawdust public bars to the floodlit stage of stadium arenas, where, watched by thousands whose adrenaline levels are stoked by copious amounts of alcohol and the slings and barbs of outrageous social media, the arrows fly in a bearpit of raucous gladiatorial combat.

I wish I could speak with Julie Henry about this. But she, like many of the places and spaces she used to document with such affection and clarity, is now gone. But looking back at This Sporting Life and the wider legacy she has left behind her makes me believe that that spirit lives on in other ways. It is interesting to reflect that, as patterns of consumption and spectatorship become ever-more technologically mediated, a younger generation that has grown up seduced and enmeshed by the power of the internet is seeking out the analogue attractions of board-game cafes and crazy-golf theme bars as sites to meet and socialise. I wish I could speak with Julie Henry about this, as I know she would have something interesting to say on the matter. As she would about the persistence of other, older communities, the social clubs and shared interest groups that offer crucial points of kinship and human connection among the anomie and atomisation of contemporary life. We might speak, too, about the fact that arts funders have belatedly woken up to this overlooked groundswell of untapped talent and ‘everyday creativity’ while lamenting also how the politics of inclusion they so regularly advocate often prescribes a one-size-fits-all rubric of ‘engagement’ that is as insidious, in its own way, as the terms and conditions of any technology corporation or the blandishments of any media company.

Julie and I would be having that conversation in a pub, I guess, though maybe not indoors this time, but outside in the garden, in the sunshine. The conversation would probably include a rumination on how quickly time passes, but how the good times stay with you to the end. There is a well-known saying that proclaims that life isn’t all beer and skittles, as if to warn that it is not all fun and games, and that you need to work extra hard to avoid frittering it away. As Julie Henry’s joyful, evocative art affirms, though, fun and games, and the consolations of pleasure and leisure, matter more than ever to a huge mass of people whose working lives and daily struggles to get by make them yearn for some all-too-precious time in which they can truly and properly be themselves. Above all else, Julie Henry’s work, generous to a fault, and tender and stirring in equal measure, reminds us that people live for these precious moments. But, even more poignantly, it also assures us that these precious moments live on.

--

Steven Bode is the former Director of Film and Video Umbrella.