Implicated

Natasha Hoare

Goldsmiths CCA curator Natasha Hoare explores the work of Richard Whitby and asks who is implicated in the UK immigration act.

Projects

“Please verbally confirm that you want to be a resident of the greatest country in the world.”

Titled after a short story by Samuel Beckett, Richard Whitby’s new work The Lost Ones satirically interrogates the absurd bureaucracies at work in the UK immigration system. Here, citizenship is tested in an encounter that demands total compliance. Participants must sacrifice their most private of thoughts in an invidious cycle of question and answer in which there seems no way of winning. Throughout the moving-image work Whitby brings a dystopian Orwellian vision of state surveillance and doublespeak to bear on Brexit Britain and its narratives around immigration – threaded through with gallows humour. Periodically overlaid with footage showing an animated creature – the implied source of the interrogation – the film moves into territory occupied by auteurs such as Jan Švankmajer, whose dark and surreal works were threatening enough that they earned him outright censorship in his native Czech Republic: “The only fitting answer to the cruelties of life is to ridicule them by using your imagination.”

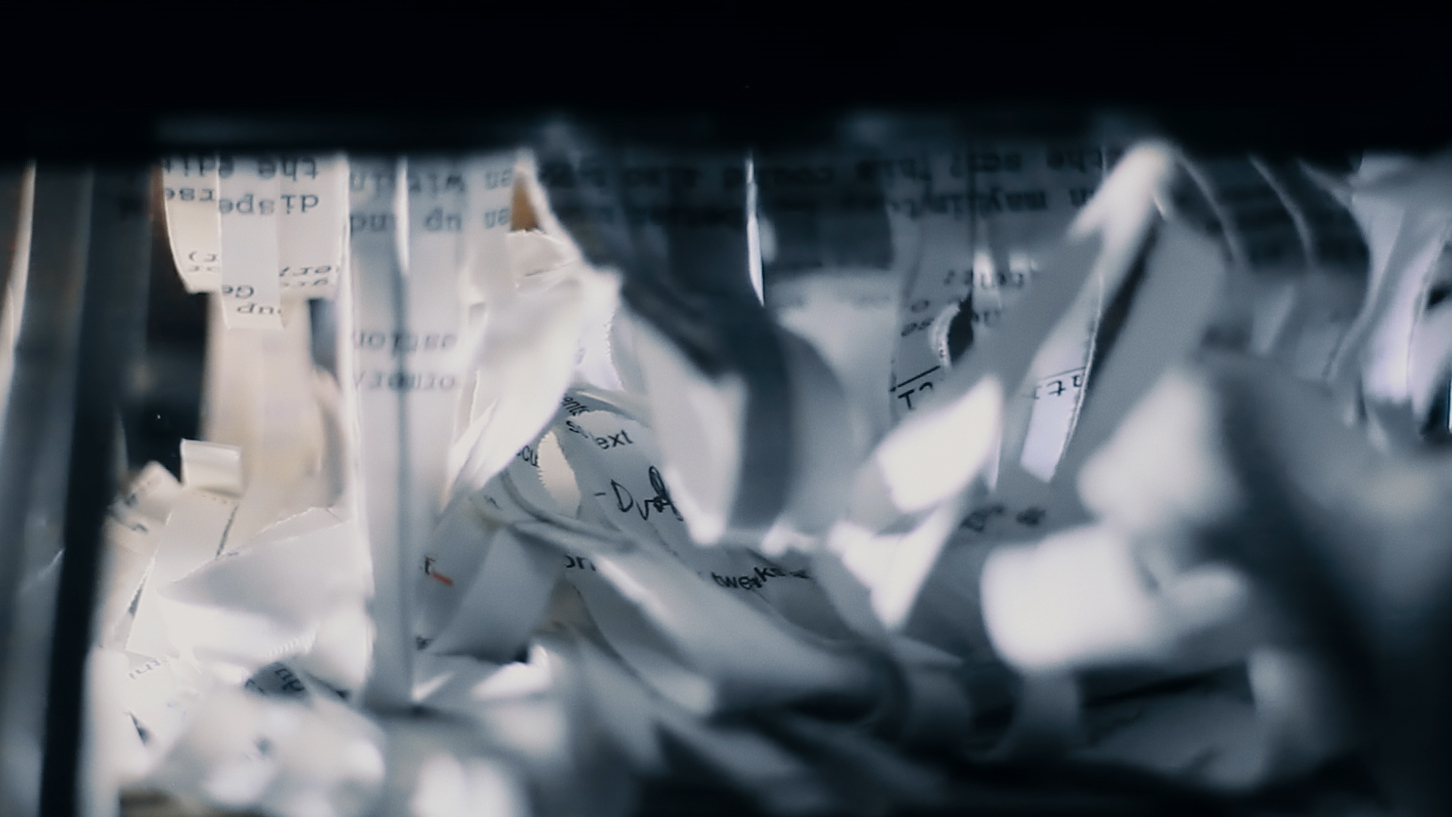

A locked-off shot frames a waiting room. The space is typical of those that stage the play of power between citizen and state. A printer, magnolia papered walls, a row of cheap chairs: the drab backdrop of a thousand human dramas. We cut back and forth between scenes in which men and women attempt to perform the role that the state demands of them. Or they wait... and wait; some sleep, others fight or break down. Each application is one chapter of a purgatorial story that has no end. Fittingly, the film structurally enacts this interminable nature through its looping in the exhibition space. The applicants are judged and tormented by a capricious disembodied voice that not only asks questions, but demands they stand in a particular part of the room, or go through the additional indignity of paying for their application through an awkwardly placed card machine. Desperately, the characters try to navigate their interrogation, and the various demands that govern their fate, decided by a voice whose register moves between officious and sadistic.

We look in on the applicants as if seeing them on a stage; a perspective that cues a reading of their behaviour as performed, the statements demanded of them performative utterances that enact or activate their status as citizen. The final say, however, rests with the demonic voice as the absolute arbiter. Each participant in this nightmarish labyrinth is subject to impenetrable demands and needlessly intrusive lines of questioning; ‘Do you plan to start a family?’; ‘What is your sexuality?’ The script was developed with satirist Alistair Beaton, and draws from various state documents including actual immigration forms, Personal Independence Payment assessments, and the infamous Life in the UK Test. The latter draws on an instrumentalised version of UK history, to which its applicants must subscribe, a fact hinted at in the careful positioning of a framed image of a castle on the wall in the waiting room.

Sound plays an integral role in building tension throughout the film, heightening the psychic strain each applicant is under. The voice itself distorts heavily in places, and when someone has not paid enough attention or answered fast enough it screams. The oppressive nature of the space is further augmented by a scratchy and unsettling string and foley soundscape created by Lucy Railton, and through the deft manoeuvre of contact mic’ing the floor of the set. Consequently every step taken by an actor is amplified. The floor seems to creak as if this is a very flimsy set, enhancing the sense of another presence just a thin plywood wall away.

Our position as a viewer does not exempt us from the moral matrix of the work. The frontal perspective of the majority of the shots in the film also forces us into the position of the interrogator. As spectators we are deeply implicated in the power structure the directional camera imposes on us. Whitby here implies that our nation’s policy on migration is, in our lack of coherent political response or action, a moral contagion, a problem located within each of us. The ‘lost ones’ are not just those victims of this system. As a society that purports to have built a judicial system that expresses our values, we, too, may be said to have lost our way. As such the film is a shot across the bows of UK society, but more specifically a fictionalised lampooning of asylum and immigration tribunals, an out-of-sight judiciary process, one that has been exposed as subject to the whims and prejudices of those conducting the interviews, as well as a political football. Within this landscape a plethora of private immigration law firms have sprung up, and tellingly in the film those who can afford an immigration lawyer are the only ones to be released from the system.

This main action of the film is periodically overlaid with stop frame animation and shots of a space seemingly behind the walls of the room. Flashes of a clawed hand, gnawing teeth, and white fur are revealed to belong to a strange creature who is implied as the source of the interrogator’s voice. Here, Whitby draws on the story of Gef, a paranormal mongoose reported by a family living on the Isle of Man in the 1930s. According to the family, Gef scratched behind the walls, moved objects around the isolated house, and spoke to them in several languages – his chattering veering from the clairvoyant to the malevolent. The story became nationally famous through the tabloid press, and experts in paranormal phenomena made their way to the farmhouse to investigate. All ‘proof’ of the mongoose, including hairs and paw prints, was shown to belong to the family dog. Some concluded that the animal was fabricated by the daughter of the family, Voirrey, who was using ventriloquism to impersonate the creature, and that the family were monetising the situation. This bizarre history activates a sense of the imaginary, of psychic splitting, all hinting that the protagonists in the The Lost Ones may well have imagined their interrogator. This ambiguity complicates the narrative of the film, suggesting that the lexicon of native / non-native, migrant / citizen are artifices we have built that imprison us all in a narrative of fear and subjugation.

Whitby’s process is a considered one, and integral to the content of the film. The actors, some of whom are not formally trained, improvised their way through the situation and had not encountered the set, including the amplified floor, before the shoot. A few of the performers look visibly shaken by their interaction with the interrogator. Just as the script blurs fact and fiction, so the line between real emotions and performed ones is unclear.

The decision Whitby made to cast actors with UK accents allows a further critique, one that holds us all ultimately accountable for systems – judicial, bureaucratic, political, ethical – that have finally turned on us in a total breakdown of the social contract. The Lost Ones thus operates as a satirical portrait of UK social morality figured as a carnivorous creature motivated by a cruel logic of intolerance and prejudice.

–––

Natasha Hoare is Curator at Goldsmiths Centre for Contemporary Art, London

This text was written in response to The Lost Ones (2019) by Richard Whitby, which was commissioned for the Jerwood/FVU Awards 2019: Going, Gone, a collaboration between Jerwood Arts and Film and Video Umbrella.