Interrupting the Pan: Marine Hugonnier’s 'Ariana'

Michael Newman

In this essay, critic Michael Newman traces the evolution of the panorama and its importance as a motif in Marine Hugonnier’s beautifully rounded portrait of Afghanistan.

Projects

Just before launching the airstrikes, the U.S. Defense department purchased the rights to all available satellite images of Afghanistan and neighboring countries... The CEO of Space Imaging Inc. said, ‘They are buying all the imagery available.’ There is nothing left to see. [ i ]

The satellite image is the apotheosis of the overview, and the impetus for its development was the desire for military domination and control. It is no coincidence that in the 19th century a craze for balloons accompanied one for panoramas. Balloon and panorama were different but complementary: the former offered an overview of the landscape, the latter an immersive experience that replaced it; but both were in pursuit of control through a view that was as total as the technology of the time allowed. The military uses of the balloon are well known; less obvious are the military connections in the origins of the panorama. Just over 250 years ago the brothers Paul and Thomas Sandby travelled in the Highlands of Scotland, where the Jacobite Rebellion had been crushed in 1746, for the Military Survey, using a camera obscura to make accurate renditions of the terrain, including panoramic views. "Only detailed cartographic data," Olivier Grau writes, "could be used effectively to play through questions of tactics, field of fire, positions for advance and retreat, and the like...”[ii] He goes on to describe how, after the first public exhibition of a panorama by Robert Barker in London in 1793, Paul Sandby, who must have been familiar with Barker's invention, went on to create a ‘room of illusion’ by covering the walls with a wild and romantic landscape, without framing elements.[iii] Barker also had military affiliations: his studio in Edinburgh was the Guards Room of the castle of a high-ranking military officer, Lord Elcho, at Holyrood, and it was there that he made the first panorama, a 21-metre-long, 180-degree view of the city. "Thus, the inception of the panorama was characterised by a combination of media and military history."[iv] True to its military origins, one of the most popular subjects for panoramas, in addition to cityscapes and exotic foreign countries, was battles.

The Crimean War of 1853-56 was the first battleground to offer itself as a subject for photography. Since the long exposure times of early cameras meant that the fighting itself could not be captured, photographers often resorted instead to a study of the surrounding landscape, a landscape that was for the most part depicted as empty of people. Jean-Charles Langlois, a retired French colonel and a battle painter who was commissioned with Louis Mehedin to create a panorama of the siege of Sebastopol, took a panoramic series of photographs of Sebastopol from a tower surrounded by sandbagged fortifications, so the viewer is placed in the position of a soldier.[v] However, the ruined and disordered state of the defences suggests not a battle in progress or to come, but rather the deserted aftermath. In making his painted Panorama of Sébastopol (1856), Langlois used projections of photographs.[vi] In 1862-63, Langlois prepared a painted panorama on the basis of topographical photographs of the 1859 Battle of Solferino between the French and the Austrians.[vii] Concurrently, in the United States Civil War of 1861-65, photographers formed part of the topographical section of General Sherman’s Union army, providing images to help draw up maps and plans.[viii] Later, during the First World War this surveying function was supported by aerial photography.

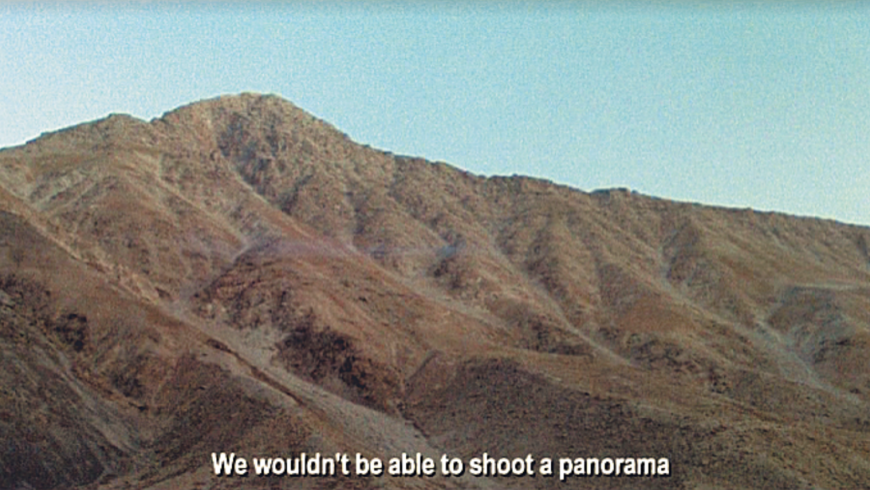

The first shot in Marine Hugonnier's film Ariana is a view from an airplane window of a dry mountain range. Later there is a shot that is an extended pan of a location in the lush Pandjsher Valley in Northern Afghanistan. We are told in the voice-over, as translated by the subtitles, “Neither of the two revolutionary utopias which had ruined the country had ever entered this place”,[ix] and it is suggested that this is because it is “protected by its mountains.” What we are shown – the fertile valley, and later on boys swimming in the river – appears idyllic, as if in reference to traditional depictions of paradise, which doesn’t exclude the possibility that this is an outsider’s idealisation. The pan transforms this idyll into a strategic terrain. The voice-over says:

In the light of coming battles, the landscape took on a strategic aspect./ Every contour of land, pass and gorge, every shadow of a rock, lookout and footpath, was seen as a potential shelter,/ a hiding place, or a line of approach to be hidden from enemy eyes./ Each specific feature, hollow, mound and viewpoint was thought of as a zone to control, a forward position to hold, a place to fall back to.

And then the question is posed:

And if the best point of view was not accessible to us, was it because it was also a strategic point?

The mountains provide a potential vantage point for the pan, the name for a rotating shot (from the Greek pan meaning ‘all’), which translates to panoramique in French, making the connection with the panorama explicit (adding horãma, sight, from horãn[MN1], to see, hence ‘sight of all’, implying that everything is available to vision). Even before the word was used, probably around the turn of the 19th century, for the painted panorama, Horace-Bénédict de Saussure, in his Voyages dans les Alps (1779-96), referred, in Bernard Comment’s words, “to panoramic viewpoints from which the whole of a landscape could be recaptured at a glance,” and devised a way in which a 360-degree view could be represented on the page.[x] But the mountains are also a site of resistance. It is this duality that will be explored in Ariana, where there is both a struggle for the panorama, and a resistance to the panoramic as such. The film is about the failure to achieve a panoramic representation of the landscape of Afghanistan. This failure is inscribed in a ‘panoramic desire’ which is more complex than a concentration on its strategic implications would suggest. As well as being an historical form of topographic representation, with a particular genealogy going back to the camera obscura and other aids to landscape rendition and forward to the cinema and on to IMAX, panoramas epitomise a structure of desire, the desire for totality, for the transformation of the world into a total, unbroken image, with the subject at its centre. This desire is paradoxical, since it is both a desire for the Other, and a desire to reduce the Other to the same.[xi]

This duality articulates itself around the idea of the horizon. It has been argued that the origin of the panorama coincides with the discovery of the horizon as a unique experience. In his Italian Journal Goethe wrote in the entry of March 30, 1787, on his first sea voyage:

No one who has never seen himself surrounded on all sides by nothing but the sea can have a true conception of the world and his own relation to it. The simple, noble line of the marine horizon has given me, as a landscape painter, quite new ideas.[xii]

The horizon is that limit within which the world becomes a representation for the subject. It is a limit that travels with the subject, who is thus placed at the centre of the world understood as picture. As Hegel argued, as soon as a limit is posited, it is gone beyond.[xiii] The project of the West is to extend the limit by passing beyond it, infinitely. This would be a utopia of totalisation, in which everything would be a potential object for knowledge, everything reduced to a being-for-the-subject, even if that totalisation is necessarily deferred.

Clearly the panorama has historical, ontological and ethical implications, all of which are engaged by Hugonnier's film. If we ask the question ‘Why does the panorama need to be interrupted?’ the answer might include reference to its historical links with surveillance and military power; or it might refer to the Other, and the religious and ethical prohibition of the image (particularly, in this case, considering Afghanistan's Islamic heritage); or it might refer to the interruption of the homogeneity of the image by an Outside that impels the interstices of the film Ariana, the frames of black, to take on an autonomy, rather than being the invisible linkages between two clips of film.

The physiological exigencies of the panorama anticipate aspects of cinema. Painted panoramas were constructed with a viewing platform and a barrier to keep visitors at a sufficient distance so that the eye could not discriminate the surface of the canvas from the image, just as the phenomenon of persistence of vision is used to suppress the blackness on the celluloid between the photograms. In both cases the physiology of vision is exploited in order to maintain the seamless continuity of the representation. While there is clearly a distinction between the panorama and the cinematic pan, since the panorama is a laterally unframed image while film maintains its frame (which is different in its effects from the frame of both painting and still photography), moving the image within it, both panorama and pan imply a similar temporal condition, not least since the ‘still’ image of the panorama requires time to consume it by walking around the central platform. Both imply a continuous, homogenous time (a homogeneity that becomes the near-instantaneity of global, satellite time). The difference is that, while the apparatus of the panorama limits it to this positing of a temporal homogeneity, the pan is only one option for the shot, and the shot itself is subject to cutting and montage. The homogenous time of the pan may be disrupted within the cinematic form itself.

After the first failure to get the panoramic shot, in the Pandjsher Valley, “for a couple of days we became nothing more than tourists.” Of course, their panoramic desire, as well as being connected with the drive to knowledge, had already, as a spectatorial relationship to the landscape, turned them into tourists. The crew go to Kabul where, by contrast with the countryside and the mountains which are shot in 16mm, an 8mm camera is used for the city, intensifying the sense of fragility and fragmentation. Apart from battles, two favourite subjects for panoramas were exotic, far-away places—anticipations of the tourist gaze rooted in imperialism—and, from the start, the local cityscape. One reason for the mass appeal in the 19th century of panoramas of the surrounding city was that they allowed the visual mastery of an urban fabric rendered opaque, fragmented and inescapable by modernisation.[xiv] In Ariana the first visit to the city is contrasted by a second sequence, which comes after the claim that utopias are a thing of the past, where fragmentation is given a positive valency against panoramic homogeneity. The city is an ‘assembly’ of the traces of utopian ideologies, “all of them scattered in fragments.” In one of the city sequences, a series of shots with a hand-held 8mm camera, where the effect of the moving camera places us within the fragmentation and flow of what we are seeing, is contrasted with a pan with the camera fixed on a tripod.

The continuity of this shot, this panorama, seemed to erase those fragments./ It made the cityscape homogenous as opposed to this urban reality,/ as if the idea of discontinuity, or of a revolution, was impossible.

This contrast is reminiscent of Walter Benjamin’s distinction between the homogenous time of historicism (of which the panorama is the visual modality), and the ‘dialectical image’ in which there is a spark of profane illumination between discontinuous times. On the subject of panoramas, Benjamin writes that their ‘particular pathos’ concerns the relation they set up between nature and history.[xv] If, in the panorama, history becomes a second nature, then a counter-panoramic mode would present nature as intervening in history, which is not quite the same as seeing ‘nature’ as a historical category. The mountains with no name seem, for Hugonnier, to offer something other than a picturesque accompaniment to the naturalisation of history —“This landscape is never to be seen simply as décor or background.”

The panorama creates its reality-effect by combining distance with detail: the viewer is maintained at a distance from the canvas in order to preserve the illusion, yet at the same time each detail is painted with the same attention. Comment writes of a ‘double focus’ of the panorama: “the panorama was able to combine what could be seen close up with what could be seen in the distance through a conflation of the gaze which rendered the spectator’s movement towards the painting unnecessary.”[xvi] Cinema has the possibility of varying the relation with distance and nearness through the focal length of the lenses used. A long lens will create the effect of nearness with that which is far away, while a short lens will position the viewer close to the subject. Just this contrast is explored in a montage in Ariana which cuts from a group of men sitting drinking tea and talking, shot with a long lens – which implies both surveillance and tourism – to a tracking shot that moves across from a curtained window to a woman’s head-scarf and cheek. It is as if we move from being far yet near, to near yet far: while the first sequence offers a false closeness, the second sequence, which puts us beside the woman, nevertheless reminds us of the difference between nearness and proximity — however close we are to the woman, she remains other.

The painted panorama has a potential that is repressed in cinema: the possibility of reversal; since, even if the viewing platform simulates a tower or a mountain-top, the viewers are in the visible – visible to each other, and potentially at least from the field of the panorama itself – in a way that is elided in cinema. The technological passage from panorama to satellite surveillance therefore requires the mediation of cinema, with its unseen viewer (who is regarded not by the reversed look, but by the asymmetric gaze of the Other). In the form of the panorama, however, what the reversibility of the look indicates is the way in which the visitor, who has come in search of a certain mastery of the surroundings, is trapped as the subject of a purely visual simulation (the panorama takes representation into simulation since the illusion is totalized — the frame is removed, in order to avoid comparison of the image with reality). Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon, a design for a prison, dates from 1791, four years after Barker’s patent for the panorama, and is based on a similar idea of total, yet one-sided, visibility, this time to a warder at the centre of a circle of cells who is invisible to the prisoners, so that they can never be sure whether they are observed, an uncertainty that effects an internalisation of the system of surveillance, in the name of their reform. Olivier Grau remarks that in the panorama “[t]he situation of Bentham’s Panopticon is reversed…[t]he observer is the object of political control”.[xvii] Only in this case control is combined with a totalisation of the visual simulation, which would need to be broken by discourse and mutual interaction. Hugonnier’s deconstruction of the pan works in two directions: on the side of its connection with the panorama, through the blocking of the view in the name of the other; and on the side of the temporal medium of film, through the interstices (which I will discuss further below). Panoramic desire is simultaneously provoked and thrown into question. This structure of desire is also taken up in relation to the name. It is here that we can begin to discern more clearly the friction, and the play, between the panoramic and the utopic.[xviii]

‘Ariana’ is the name of the national airline of Afghanistan. It was also the name for the eastern provinces of the ancient Persian Empire, the regions south of the Oxus River — so the modern airline is named after an ancient province that no longer exists, as if the no-longer could connect with the not-yet. The film begins with an airplane sound over black leader, followed by a rather bleak and apparently barren mountain range. The voice-over tells us that "In this country mountains have no name./ You cannot tell them apart unless you group them together." Then, over black leader again, the voice says: "During the war, battles were fought to secure vantage points offering panoramas. This was the way to control the country." Then we see a hand covering the lens of the camera, obscuring our view (anticipating all those frustrations in the search for the image), followed by a plane of the Afghan airline on the ground — as if the one from which the film crew had embarked. Then the words: "This was the way to control the country. Planes had to be destroyed." Finally: "ARIANA". The name, as well as being that of the airline, itself homophonous for us with ‘air’, is the name of a woman; it also resonates with the privative ‘a’ of the a-topia (non-place) that is one side of u-topia. It is spoken as if it were the addressee of the voice, the beloved, maybe the beloved of a woman, since the voice is a woman's.[xix] The voice we hear on the film may or may not be the artist, or the fictional film director who remains unnamed among the crew ("The ones remaining are the anthropologist, the geographer, the cameraman, the sound engineer and the local guide"), or perhaps someone else entirely. The introduction of the possibility of fiction unsettles the objectification implicit in the documentary mode. The danger of documentary is the same as that of historicism (which was the discursive frame for panorama in the 19th century): namely an identification of the signified with the referent in a way that fixes ‘reality’ as that which is somehow inevitable. The insinuation of fiction separates reality from itself, introducing a distance, drawing attention to the partiality of representation, and opening up a space of possibility for the ‘no-place’ of utopia.[xx]

This question of the relation of referent to signified is developed in the film as a practice of naming. It is as if the name ‘Ariana’ were the counterpoint to the unnamed mountains. The double invocation of the ‘no-name’ and the proper name allows us to connect the relation of language to the original gesture towards the singular to the ‘uncolonised’ space of utopia. If the identification of a place depends on the name, the unnamed mountains maintain themselves, in a sense, as ‘no-place’. The word ‘utopia’ can be derived both from the Greek for ‘no place’ and for ‘good place’: it is both a negation and an affirmation at the same time, therefore neutralising the logic of opposition.[xxi] To introduce a ‘no-place’ into the mapped, named and described places of the world – and the ‘exotic’ has served as the provocation for just such an imperialist project, a project that from all sides repeatedly stumbled over Afghanistan – is to open a space for utopia, as ‘good place’. Such a space would be of a peculiar kind, since it would have to interrupt the continuity at which the mapping of ‘panoramic’ space aims. It would be a space that interrupts space, and since interruption has a temporal dimension, this would amount to an irruption of time into space. If desire needs an object, yet must not ‘objectify’ that object, turn it into a fetish, in the sense of a false god, then ‘Ariana’ might name the impossible non-object of utopian desire. It is also, mundanely, the name of the rather run-down Afghan airline, and is therefore inscribed in a specific history of statehood, and the possibility for Afghans to attain their own access to power and a place in the international world. The film works on an edge between the actual politics of the everyday world and a kind of absolute claim, a utopia that cannot be reduced to any of the historical ‘utopias' whether Communist, religious or consumerist. Over the image of a ruined, dried-up concrete swimming pool, with the diving boards filmed from below in heroic Constructivist fashion, a passage of voice-over goes:

All throughout our trip back to the city, our guide told us about his country, his hopes, while promises of past ideologies filled the landscape./ We grew up insulated by liberalism. We have no political ideology anymore. No project./ Utopias are only a legacy. We have nothing left to hope for from them.

The ‘we’ speaks the despair of a generation in the West that watches the news from Afghanistan, or Iraq, on CNN or BBC, without being able to connect it to a collective political project of resistance. Yet the film also works against this despair in its maintenance of utopic desire, the desire that goes under the name ‘Ariana’, and is willing to leave the mountains unnamed.

Utopic desire must neutralise the terms of opposition that have determined the historically existing attempts to realise utopia. This interruption is a formal operation, a work in and on the medium. Interruption works in a multiplicity of ways in Hugonnier's film. First, there is the simple interruption of the cut within sequences, which tends to evoke a contact, for example between a far and a near view, or between the world of men and that of women. Second, there are the sequences of black leader. Sometimes the soundtrack continues over these, with or without the voice-over in French. Often these black sequences contain the English subtitles. Once we read "(Distant explosions)” but hear no sounds. In this recourse to written description, which is in effect a caption that follows the image, and that is in a certain sense without image, writing takes on an autonomy, as if the black screen were a negation of the image, that requires an alternative expression, one that would not fetishise what is represented. A further complication is introduced if we know – or perhaps sense – that the following sequence, which included flashes of red, was not in fact footage of a battle: this insinuates into the film a certain undecidability between fact and fiction.

If the pan is understood as a modality of documentary, then the question arises both of the status of what we are seeing, and of the objectifying implications of documentary, its reduction of otherness to image, which has been contested in the films of Jean Rouch, including fabulations created by the subject-participants themselves as well as foregrounding the position and involvement of the anthropologist: truth is not objectively given in facts and data, but provoked through fiction and enactment. Jean-Luc Godard mentioned Rouch’s 1957 film Moi, un noir in support of his dictum that “all great fiction films tend towards documentary, just as all great documentaries tend towards fiction.”[xxii] Godard also contrasted Rouch to the ‘classicist’ film-makers Eisenstein and Hitchcock: “The others, people like Rouch, don’t know exactly what they are doing, and search for it. The film is the search.”[xxiii] It is no coincidence, then, that the team in Ariana that sets out to film in Afghanistan includes not only a geographer (recalling the topographic origins of panorama), but also an anthropologist. In traditional terms – critiqued by Rouch and others – these are emblematic of those who set out to transform the land and those who inhabit it into objects of discursive knowledge, a project that, in the course of Hugonnier's film, remains frustrated with the inaccessibility of the panorama. The possibility of another kind of relation is suggested by the film show to which the crew is invited: what is presented is a film of tropical fish swimming in their habitat (Afghanistan does not have a coastline, so this is another desired, inaccessible point of view). The camera moves underwater, ‘with’ the fish, yet at the same time the viewer is separated. The image is ambivalent: on the one hand, the ’medium’ provides the possibility of a connection with the Other and the alien[xxiv]; on the other hand, the immersive is the form that is anticipated by the panorama, culminating in the rotunda Claude Monet specified for his Waterlilies — he wanted to decorate a drawing-room in a way that ‘would have produced the illusion of a whole without end, of a wave without horizon and without shore... a haven for quiet meditation at the centre of a flower-filled aquarium.”[xxv] So this sequence could provide an alternative to the panorama, or its destiny: being-with-the-other, or immersive experience with no outside, undecidably. What the underwater sequence in the film-show presents is immersion without totality; tellingly it is followed by the city shots using a hand-held camera.

Finally, permission is obtained to climb ‘Television Hill’ — we are shown the letter of permission being written in Arabic script, reminding us of the role of calligraphy in a culture that restricts the image, in contrast to the global dissemination of the image through broadcasting (near the beginning of the film we hear, on the soundtrack, a snatch of the London news). In this last attempt in the story to attain a panoramic representation we are shown a view from above the city to the mountains – although not a pan – and told that “The entire landscape was like a still image, a painting./ This spectacle made us euphoric and gave us a feeling of totality.” In the painted panoramas, it was both important both that the view from the platform be uninterrupted, and that the visitors, as the subjects of a homogenous view, form a unity, a collective subject. The ideology of the panorama was in effect to unify the publics of the 19th century nation-states of the West in the age of imperialism. Here, however, the summit is shared with the Afghan soldier who has accompanied the crew and "stood proudly in front of the view." It is as if his presence in the image reflects attention back onto the ‘invisible’ film crew, and interposes a difference where there may have been a presupposition of unity. This provokes the question of who ‘owns’ the view: if the viewers are not one, who has the right (remembering the earlier legal transaction of the ‘permission’) to this point of view, this panorama? The film crew must abjure the temptation of euphoria, the lure of totality. Whereupon, “We gave up filming.” The screen goes black.

Is this a moment of frustration, or an act of self-denial? At stake is whether we can still – or once again – speak of an ethics and politics of form. In a group discussion about Marguerite Duras’ and Alain Resnais’ film Hiroshima mon amour (1959) in the year that it appeared, Jean-Luc Godard stated that “tracking shots are a question of morality.”[xxvi] The question of the ethical and political implications of a particular kind of shot was taken up two years later by Jacques Rivette, in a review of Guillo Pontecorvo’s film Kapo entitled ‘De l’abjection’,[xxvii] where the question was that of a forward tracking shot when a character commits suicide: “Look at Kapo, the shot when Emmanuelle Riva commits suicide by throwing herself on the electrified wires: someone who decides at that moment to do a forward tracking shot to reframe the body from beneath, taking care to set the raised hand exactly in a corner of the final frame, deserves nothing more than the deepest contempt.”[xxviii] The critic Serge Daney returned to the controversy around this claim in his essay ‘Le traveling de Kapo’,[xxix] where he adds, “Thus a simple camera movement was the one not to make. The movement you must – obviously – be abject to make. As soon as I read those lines I know the author was absolutely right.”[xxx] That Kapo is, as Daney states at the outset “among the movies I have never seen,” far from qualifying his statement, reinforces it, since there are things that should not be shown, or at least are not to be represented in an image that does not speak of its own limitations. But is Rivette still right today? The moment of assent to this doctrine is situated by Daney in relation to his own birth as a cinephile at a time when, between Auschwitz and Hiroshima in the near past, and the looming threat of nuclear annihilation, the essential thing seemed to be an aesthetics and politics of form. Daney contrasts the tracking shot in Kapo, a camera-movement that aestheticizes a dead body in a way that obliterates singularity, with the distance maintained by Resnais’ film on the Holocaust, Nuit et Brouillard (1955), although he sees the way in which that film is wheeled out as a touchstone whenever anti-semitism is raised in France as problematic, and the piles of bodies in that film too close to the pornographic beauty of the Western Christian tradition of painting. A less reserved contrast is with Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu (1959), where Miyagi’s death “seems so accidental that the camera almost misses it,” which stresses the contingency over the sublimation of death. The final movement of Daney’s essay begins with the image of the video of the 1985 Live Aid concert: “The rich singers (“We are the world, we are the children!”) were mixing their image with the image of the skinny children. Actually they were taking their place; they were replacing and erasing them.”[xxxi] Does the lesson of the immorality of the tracking shot in Kapo still apply? “In Kapo it was still possible to be upset at Pontecorvo for inconsiderately abolishing a distance he should have ‘kept’. The tracking shot was immoral for the simple reason that it was putting us – him filmmaker and me spectator – in a place where we did not belong, where I anyway could not and did not want to be, because he ‘deported’ me from my real situation as a spectator-witness forcing me to be part of the picture. What was the meaning of Godard’s formula if not that one should never put himself where one isn’t nor should he speak for others?” We should be careful not to equate this distance with detachment. Cinema ‘adopted’ him, Daney writes, “So that it could teach me to tirelessly touch with my gaze the distance from me at which the other begins.”[xxxii] In this distance resides the distinction between identification, with the consolations of sympathy, and respect for the other as other. In Ariana, Marine Hugonnier shows herself to be concerned in an exemplary way with the “distance from me at which the other begins.” Is not the problem with the pan, finally acknowledged on ‘Television Hill’, precisely that it would put us “in a place where we did not belong”? Just over a decade after the moment when for Daney, who died of AIDS in 1992, the year the aforementioned essay was published, it seemed that “tracking shots are no longer a moral issue” and “cinema is too weak to entertain such a question,” Hugonnier returns, in the context of a new imperialism, to the ethics and politics of form.

The final interruption of the panorama gathers together the interruptions at the level of the story, and another level of interruption, which is connected in formal terms with the interruption by the interstice.[xxxiii] The ‘between’ becomes an interstice when its role exceeds that of joining two clips of film, rendering itself invisible or suppressed by means of continuity and suture, for example by maintaining subjective continuity by means of a structure of shot and counter-shot. The interstice ceases to relate to the ‘whole’ of the film – that implied, if ever-receding, totality of the shots – and refers to the Outside, as its very intervention. It is no coincidence that the intervention of the Outside in the interstices relates to the sense of failure, frustration and lassitude of the film-crew: it is in the context of the failure of their attempt to attain the totalised horizon of the panorama that the ‘between’ of the images figures as something other than the linkages of continuity and interrupts the seamlessness of representation. The homogenous time of the panorama is related to a past that is ‘my’ past, and a future that is essentially a projection of the present. As the voice-over says, against an image of the blue sky:

After all, doesn't a high point of view allow the possibility of projecting a future into space?/ Wasn't it also the sweet memory of the tourist attraction that wasn't to be missed on holidays when we were children?

Nostalgia here is related to the transformation of the landscape into an image to be consumed, a ‘tourist attraction’. Landscape is transformed into a souvenir out of a denial of loss, which is also the denial of the possibility of a fracture in the continuity of time, of a revolution. The homogeneity of the panorama implies the attempt to control the future by reference to that which was. The interruption of the panorama at the level of the interstice, as an intervention from the Outside, might imply the opening up of the future to the other and the unprecedented, the ‘utopic’ as distinct from the failed historical utopias, which are ‘panoramic’ in their attempts at the totalisation of past and future. We are left with the image of the crew’s car, ‘FILM’ taped in large letters on its windscreen, abandoned with its doors open in the midst of an urban housing development. Around it people walk by and local boys play soccer. The shot is a fixed one, which emphasises the non-visibility of the out-of-frame from which passers-by emerge and into which they disappear, and therefore, as opposed to the attempt of the pan to show all, the limits of the image. The credits roll. Life goes on.

[i] David Levi Strauss, Between the Eyes: Essays on Photography and Politics (New York: Aperture, 2003), p.190.

[ii] Olivier Grau, Virtual Art: From Illusion to Immersion, (Cambridge, Mass. and (London: The MIT Press, 2003), p.53.

[iii] Ibid, p.55. .

[iv] Ibid, p.57. .

[v] See Joëlle Bolloch, Photographies de guerre (exhibition catalogue, Paris: Musée d’Orsay, 2004), pp.11-12, and plates 14-19.

[vi] Hélène Puiseux, Les figures de la guerre: Représentations et sensibilities 1839-1996 (Paris: Gallimard, 1997), p.94. She concludes concerning the photographs of the Crimean War that “they don’t speak of heroism, they don’t say that one dies there, they say that one lives there, that one loses time there, that one kills time there and not only human beings” (p.97).

[vii] See Voir/ne pas voir la guerre: Histoire des representations photographiques de la guerre (exhibition catalogue, Paris: Somogy, éditions d’art and Bibliothèque de Documentation Internationale Contemporaine, 2001), pp.38-9. The Battle of Solferino was witnessed by the Swiss philanthropist Henry Dunant, an experience that led to his promotion of the Red Cross, founded in 1864. An early action of the Red Cross was the care of the sick and wounded of the defeated French army under General Bourbaki of the Franco-Prussian war, which was given asylum in Switzerland in 1871, an event that formed the subject for the remarkable panorama painted by Edouard Castres, which opened in Geneva in 1881, and was moved to its current location in Luzern in 1889. This panorama is shown being restored by women in Jeff Wall’s large back-lit Cibachrome transparency Restoration (1993). Formal and thematic aspects intersect: Wall’s photograph folds the acts of care depicted by Castres back into the picture itself, while at the same time indicating, by its inability to depict the 360-degree panorama, that there is a limit to what can be shown in the flat image. Wall has said in an interview: “The fact that the panorama can be seen escaping from view is one of the things which most interested me in making the work. The idea that there is something in every picture, no matter who well-structured the picture is, that escapes being shown” (“’I am not necessarily interested in different subject matter, but rather in different types of picture’: Jeff Wall interviewed by Martin Schwander,” in Jeff Wall: Restoration [Kunstmuseum Luzern and Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, 1994], p.25). Wall’s way of indicating the limit depends on his image being still, which does not mean that there is not also something that escapes the moving image, and therefore equally an ethics of form. When Wall first saw the Bourbaki panorama, he was working on Dead Troops Talk. A vision after an Ambush of a Red Army Patrol, near Moquor, Afganistan, Winter 1986 (1991-92), which in turn refers to the early history of war photography and its relation to painting.

[ i ] David Levi Strauss, Between the Eyes: Essays on Photography and Politics (New York: Aperture, 2003), p.190.

[ii] Olivier Grau, Virtual Art: From Illusion to Immersion, (Cambridge, Mass. and (London: The MIT Press, 2003), p.53.

[iii] Ibid, p.55. .

[iv] Ibid, p.57. .

[v] See Joëlle Bolloch, Photographies de guerre (exhibition catalogue, Paris: Musée d’Orsay, 2004), pp.11-12, and plates 14-19.

[vi] Hélène Puiseux, Les figures de la guerre: Représentations et sensibilities 1839-1996 (Paris: Gallimard, 1997), p.94. She concludes concerning the photographs of the Crimean War that “they don’t speak of heroism, they don’t say that one dies there, they say that one lives there, that one loses time there, that one kills time there and not only human beings” (p.97).

[vii] See Voir/ne pas voir la guerre: Histoire des representations photographiques de la guerre (exhibition catalogue, Paris: Somogy, éditions d’art and Bibliothèque de Documentation Internationale Contemporaine, 2001), pp.38-9. The Battle of Solferino was witnessed by the Swiss philanthropist Henry Dunant, an experience that led to his promotion of the Red Cross, founded in 1864. An early action of the Red Cross was the care of the sick and wounded of the defeated French army under General Bourbaki of the Franco-Prussian war, which was given asylum in Switzerland in 1871, an event that formed the subject for the remarkable panorama painted by Edouard Castres, which opened in Geneva in 1881, and was moved to its current location in Luzern in 1889. This panorama is shown being restored by women in Jeff Wall’s large back-lit Cibachrome transparency Restoration (1993). Formal and thematic aspects intersect: Wall’s photograph folds the acts of care depicted by Castres back into the picture itself, while at the same time indicating, by its inability to depict the 360-degree panorama, that there is a limit to what can be shown in the flat image. Wall has said in an interview: “The fact that the panorama can be seen escaping from view is one of the things which most interested me in making the work. The idea that there is something in every picture, no matter who well-structured the picture is, that escapes being shown” (“’I am not necessarily interested in different subject matter, but rather in different types of picture’: Jeff Wall interviewed by Martin Schwander,” in Jeff Wall: Restoration [Kunstmuseum Luzern and Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, 1994], p.25). Wall’s way of indicating the limit depends on his image being still, which does not mean that there is not also something that escapes the moving image, and therefore equally an ethics of form. When Wall first saw the Bourbaki panorama, he was working on Dead Troops Talk. A vision after an Ambush of a Red Army Patrol, near Moquor, Afganistan, Winter 1986 (1991-92), which in turn refers to the early history of war photography and its relation to painting.

[viii] Bolloch, Photographies de guerre, p.13.

[ix] Quotations without a source being given are from the voice-over to Ariana.

[x] Bernard Comment, The Panorama (London: Reaktion Books, 1999), pp.81-2.

[xi] The great exploration of panoramic desire and its frustration in literature is of course Marcel Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu, as is noted in Ibid, p.143.

[xii] Cited in Stephan Oettermann, The Panorama: History of a Mass Medium (New York: Zone Books, 1997), p. 7-8.

[xiii] G.W.F. Hegel, Hegel’s Logic, trans. William Wallace (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975), §60: “No one knows, or even feels, that anything is a limit or defect, until he is at the same time above and beyond it.”

[xiv] For a discussion of this, see Comment, The Panorama, pp. 134-38.

[xv] Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project (Cambridge, Mass. and London: Harvard University Press, 1999), p 363. For a discussion of ‘dialectical images’, see Michael W. Jennings, Dialectical Images: Walter Benjamin's Theory of Literary Criticism. (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1987), p.363.

[xvi] Comment, The Panorama, pp.113.

[xvii] Grau, Virtual Art, p.111.

[xviii] The term ‘utopic’ comes from Louis Marin, Louis, Utopics: The Semiological Play of Textual Spaces (Atlantic Highlands, N.J.: Humanities Press International, 1984) to which the discussion below is indebted.

[xix] In this mode of address there is perhaps also a very muted hint at the 13th century love poems of Jalal al-Din Rumi, founder of the Mevlani Sufi order of Whirling Dervishes, who was born in Balkh in what is now Afghanistan, and who offered a way to God through longing and ecstatic sexual passion. The appeal of Rumi, who enjoyed something of a cult in the West during the 1990s, has something to do with a utopian fusion of the spiritual and the sexual. His poems are today frequently to be heard on radio stations in Kabul and Mazar-I-Sharif (See Amy Standen, “Rumi: No.1 in Afghanistan and the USA,” in salon.com at

http://dir.salon.com/people/feature/2001/10/12/barks/index.html?pn=1

[xx] See Ibid, pp.86-7.

[xxi] For the relation between utopia and the neutral, see Ibid, pp. 3-30.

[xxii] Cited in Peter Wollen, Paris Hollywood: Writings on Film (London: Verso, 2002), p.99.

[xxiii] “B.B. of the Rhine” in Jean Narboni and Tom Milne, eds., Godard on Godard: Critical Writings by Jean-Luc Godard (New York: Da Capo Press, 1986), p.101, cited in the excellent obituary by Emilie Bickerton, ‘The Camera Possessed: Jean Rouch, Ethnographic Cinéaste: 1917-2004’, New Left Review, second series, no. 27, May-June 2004, pp.49-63.

[xxiv] In an email to the author, Hugonnier related this sequence to the nature documentaries of Jean Painlevé, whose film The Sea Horse (1934) was one of the first films to use underwater footage.

[xxv] Quoted in Comment, The Panorama, p.145.

[xxvi] Jean Domarchi, Jacques Doniol-Valcroze, Jean-Luc Godard, Pierre Kast, Jacques Rivette, Eric Rohmer, ‘Hiroshima, notre amour’, Cahiers du Cinéma, no. 97, July 1959 (translated in Jim Hillier ed., Cahiers du Cinéma: The 1950s: Neo-Realism, Hollywood, New Wave (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1985), p.62. Luc Moullet, in an article on Samuel Fuller, had already claimed that “morality is a question of tracking shots” (Luc Moullet, ‘Sam Fuller – sur les brisées de Marlowe’, Cahiers du Cinéma, no.93, March 1959, translated as ‘Sam Fuller: In Marlowe’s Footsteps’ in Hillier, ed., Cahiers, p.148).

[xxvii] Cahiers du Cinéma, 20, June 1961), reprinted in Alain Bergala et al., Théories du cinema (Paris: Cahiers du cinema, 2001), pp.37-40.

[xxviii] Ibid, p.38.

[xxix] Traffic, no. 4, autumn 1992, reprinted in Serge Daney and Serge Toubiana, Persévérance (Paris: P.o.l., 1994), pp., 15-39, citations from the English translation by Laurent Kretschmar, ‘The Tracking Shot in Kapo’ at www.sensesofcinema.com/contents/04/30/kapo_daney.html. I thank Pierre Huyghe for drawing my attention to the relevance of this text to the discussion of Hugonnier’s film.

[xxx] Daney, Persévérance, p.16.

[xxxi] Ibid, p.37.

[xxxii] Ibid, p.38: “Pour qu’il m’apprenne à toucher inlassablement du regard à quelle distance de moi commence l’autre.”

[xxxiii] My discussion of the interstice is based on Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2: The Time-Image (London: The Athlone Press, 1989), pp. 179-88. For Deleuze, the Outside is time.

[MN1] The accents over the “a”s should be a flat line.

–––

Michael Newman has a background in art history and philosophy, and is Professor of Art Writing at Goldsmiths, University of London.

Ariana was commissioned by MW Projects and Film and Video Umbrella in association with Chisenhale Gallery. Supported by the National Touring Programme of Arts Council England and sponsored by Marion and Guy Nagger and Alan Djanogly.